Upon closer examination, what is left amongst the historical wreckage of the Cold War – a period in which geopolitical anxiety about nuclear threats percolated through all aspects of modern life and culture – seems to be the persistence of its ideological dichotomy that continues to define in part the linchpin of contemporary political discourse, viz., the antagonism between actually existing socialism and laissez-faire capitalism. For this reason, it is rather tempting, when discussing the legacy of the Cold War, to overstate the irreconcilability of the two systems than to examine the critical relations that might have transcended the bipolarity of the global order. Arguing against such a reductionist approach, Christina Warning’s study entitled Thailand’s Trade Relations with the German Democratic Republic: The Example of Carl Zeiss Jena, offers a fascinating account of Thailand and the German Democratic Republic’s bilateral trade relations; by tracing the development of Carl Zeiss Jena, a high-tech manufacturer founded in 1846, she analyzes how the company, along with its bifurcation and legal disputes, had a crucial role in strengthening the economic bonds between the GDR and Thailand in the 20th century.

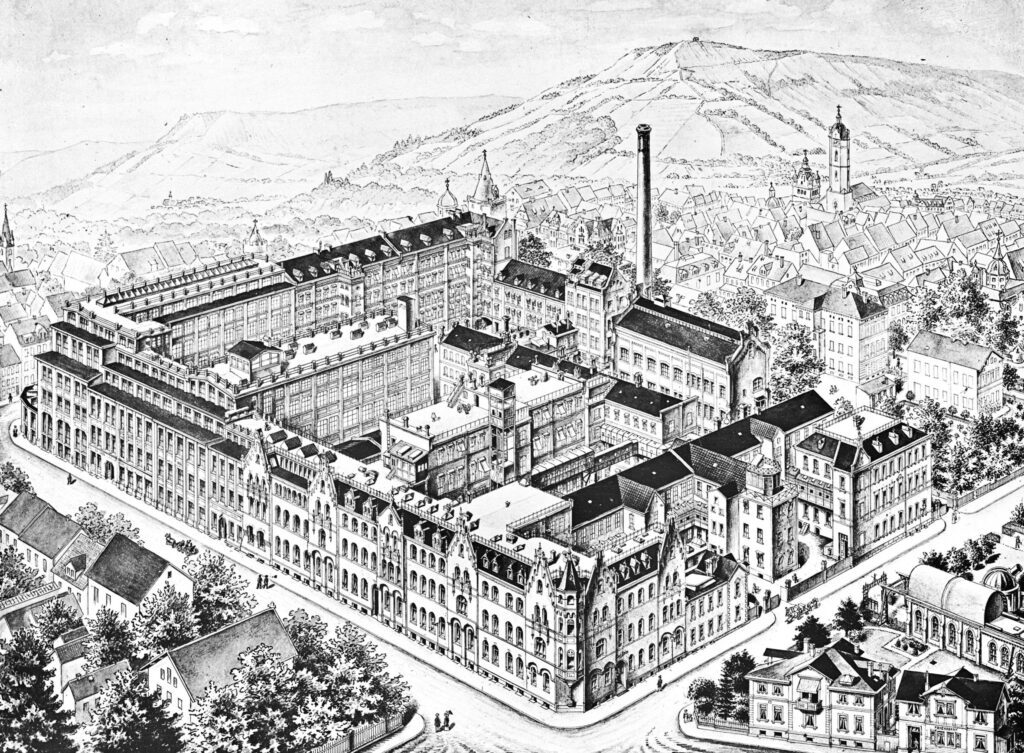

Hauptwerk von Carl Zeiss in Jena (1908) https://www.zeiss.de/corporate/newsroom/pressebilder/historische-fotos.html

The central argument put forward by the author is that, notwithstanding the political hostility between countries and their economic doctrines often at variance with one another, Thailand, to a great extent, managed to broaden and diversify its international trade relations without being subject to any ideological predilection. To take into account how Carl Zeiss Jena engaged in Thailand’s “multi-dimensional trade networks”, Warning takes the reader back to the company’s humble beginnings. A few years before the Kingdom of Siam signed a trade treaty with the Hanseatic cities of Hamburg, Lübeck and Bremen in 1858, the optician Carl Zeiss had opened a small workshop in Jena for optical instrument production. It was not until the 1930s that Carl Zeiss Jena’s good name reached Thailand, prompting King Prajadhipok and Queen Rambhai Barni to visit the company’s premises in 1934. Following Germany’s partition in 1945, the company was divided into two entities: Carl Zeiss Oberkochen, the West German branch, and Volkseigener Betrieb (VEB) Carl Zeiss Jena, the nationalized, East German branch. It was a pivotal moment in the company’s history because the two branches would be involved in protracted legal battles concerning trademark rights in the ensuing decades. Throughout the 1950s and the first half of the 1960s, the East German branch, Zeiss-Jena, failed to establish its anchor in the Thai market due to complications regarding its representatives, one of which (B. Grimm) had decided to work for Zeiss-Oberkochen instead. Zeiss-Jena was struggling to catch up with its adversary.

However, with the shifting political landscape, things started to look up for Zeiss-Jena. In 1971, Chancellor Willy Brandt and his coalition implemented a new policy of rapprochement (Entspannungspolitik) that focused on the de-politicization of trade, allowing both branches to conduct business more freely with Thailand. In a sense, the competition between the two branches encapsulated the global conflict between the Eastern Bloc and the “Free World”. But what is more interesting here is the implication that economic capital, within this context, possessed the totalizing power to subsume all the ideological boundaries and opposition. For example, the U.S.-backed Accelerated Rural Development Programme, which was utilized to ramp up anti-communist hysteria, actually stimulated economic activities with Eastern Europe and even the arch-conservative despot Thanom Kittikachorn sought to build connections with the Warsaw Pact states in 1970. With Thailand aiming to modernize itself and the GDR relying heavily on its export enterprises, it was only natural for Zeiss-Jena to go after the former’s agriculture-based economy. By 1974, the two countries successfully established bilateral trade relations as they both needed resources from each other. Although the Thanom regime came to an end in 1973, Thailand’s international trade areas remained politically unaffected since the military-influenced civilian government at the time decided to recommence trading with Eastern European socialist states. With the dawn of détente, Zeiss-Jena started to set up its nexus of institutions in Thailand, e.g., its association with the Royal Thai Survey Department. For Warning, it was this interplay between the military, private agencies and governmental organizations that led to the company’s expansion in Thailand.

Overall, Warning’s study is an impressive feat of academic prowess and rigour. With all the sections carefully laced together to construct a coherent narrative, Warning demonstrates how important economic relations are in an historical analysis of the Cold War. What she does is reveal how Thailand’s trade relations with the GDR had always been characterized by heterogeneity and, perhaps, even irony, and this aspect cannot be translated into fixed categories or understood only as “ideological persuasions”. As noted in the article, research of this kind has been scarce. Therefore, this paper, all things considered, is an immense contribution to the field of international relations.

Tanat Sangaramya